GREAT KINGSHILL 1800s

It is safe to assume that as late as 1800 Great Kingshill was simply a loose scattering of farmsteads and cottages around the edge of a common at the western end of a large open stretch of land known as Wycombe Heath, hence Heath End, as far as Penn Village to the east. An old Bucks historian described this whole area as 'an peopled wasteland'.

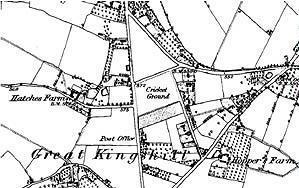

The first Ordnance Survey Map of the area published in 1822 to a scale of 1 inch to 1 mile and the much larger scaled Hughenden Tithe Map of 1844 confirm that the main part of Great Kingshill between Sladmore Farm and Cherry Tree Farm (formerly Frys Farm) was an open common area with cottages and farm buildings scattered loosely around the edge. The perimeter of this old common area can still be traced fairly accurately by a few old hedgerows and those cottages and farms which have survived such as Sladmore, Apple Tree Cottage, Claypit Cottage and Meadowcroft at the southern end. Hoppers Farm and old cottages along Common Road mark the eastern side. Arthur's Cottage, Stag House and Robin Cottage in Stag Lane, Lowlands, Ninnywood Farm, Stockens (Gibbons Farm), Cherry Tree Farm (Frys Farm) and nearby cottages are at the northern end, and Hatches Farm, 1, 2 and 3 Hatches Lane, Pipers Ash, Yew Tree Cottage, Pipers Cottage and Springfields complete the boundary. There are some more outlying cottages and farmsteads in such locations as Spurlands End, Heath End, Cockpit Hole, Pipers and Cryers Hill which are now regarded as Great Kingshill, although Cryers Hill has become a separate community over the years.

The layout of the roads as we know them today, apart from the many residential estate roads, was consolidated around the time of the Enclosure Acts which came into force in this part of Buckinghamshire in the mid-nineteenth century. The Hughenden Enclosure Act which covered most of Great Kingshill was enacted in 1855. The main road for instance, now known as Missenden Road, had progressed from a rough track across the middle of the old common to a metalled road around this time.

Turning to the local inhabitants in 1800, it is clear that the majority were engaged in farming and scratching a living from the old common. In the 1841 Census covering that part of Hitchenden or Hughenden Parish at Great Kingshill, Cryers Hill and Polecat Lane (Polecat or Knives Lane being within the parish of Hughenden in 1841) there were 69 dwellings with a population of 340 equally divided between male (171) and female (169). Of the 110 males of working age there were 4 farmers, 60 farm labourers, 8 blacksmiths and 18 involved in timber such as sawyers, wood turners, carpenters and wheelwrights. There were a few individual professions such as a baker, cordwainer, surveyor, bailiff, drover, carrier, hawker, saddle tree maker and, the pick of the bunch, a manure gatherer! The working age began at eight years old, there being no organised schooling, and finished at death, there being no such luxuries as the old-age pension or national health service.

Of the females, 70 were listed as lace-makers and these must have made a welcome or, in most cases, an essential addition to the family income. It is worth remembering that 1841 was not long after the so-called rebellion of the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834 when the average wage for a farm worker in Dorset was 10 shilling per week. It is safe to assume that the average in South Bucks would have been higher, probably 15 shillings per week or 40 pounds a year in 1841. Such small income was barely enough for a large family to live on and no doubt poaching and other forms of stealing were commonplace. It goes without saying that working conditions were extremely harsh with long hours in the field in all weathers, the normal working days being from dawn to dusk. Home comforts, apart from an open wood fire or grate with maybe an old oil-lamp or candles for lighting, were virtually non-existent. According to the 1841 Census the average occupancy rate was over five persons per household, which meant that living conditions for a large family in a small cottage, typically two rooms downstairs and two upstairs, must have been difficult.

Nevertheless, by the middle of the century there were signs of improvement and in Great Kingshill there were three important events to change the lives of the ordinary people. Firstly, the church authorities decided to build a new church and school to serve the Prestwood Common and Kingshill Common areas which were both a long way from Great Missenden and Hughenden churches, bearing in mind that the only means of travel were either on foot or by horse-back or horse drawn vehicle. At an inaugural meeting to discuss the proposal the local inhabitants of the two areas were described as "poor and ill-educated, at a great distance from their respective Parish Churches and, in the absence of proper schools, the children of the poor were almost necessarily permitted to grow up to manhood without any sufficient discipline and moral training". The new church along Knives Lane was consecrated in 1849 and the church school alongside was finished about the same time.

The second important event was the Hughenden Enclosure Act 1854 which covered most of the Great Kingshill area. The old common was "up for grabs" for want of a better term and varying land awards were made to those with legitimate claims and to some with more dubious credentials. Fortunately, that part of the common most used for cricket, football and general recreation was allocated to the local vicar, in this case the Rev. Thomas Evetts of Prestwood Church, to ensure its continued use for sport and recreation, Although now established as a recreation ground owned by Hughenden Parish Council it is still known as 'The Common' by many old Kingshillians. No doubt these dramatic changes resulting from the Enclosure Awards had a mixed reception, particularly with some of the smallholders and cottagers who had previously used parts of the old common area to graze their animals and various other activities for many years.

The third event to change the local employment pattern was the emergence of the chair-making industry in High Wycombe. With the increasing use of new farming machinery and implements involving new farming methods with less labour some small farmers and farm labourers turned to chair bodging in the nearby beech woods or, further afield, in the small back-yard workshops in High Wycombe making chairs. This drive away from farming into other trades is clearly shown in the 10 year Census from 1851 onwards. Working men living around the old common areas of places such as Prestwood, Kingshill, Holmer Green, Naphill, Downley and Booker would walk to work in High Wycombe. In the 1880s and 90s men from Great Missenden and Prestwood walked to work in High Wycombe, a distance of 7 to 8 miles, and then walked back again in the evening after a hard days work calling in at the Polecat en-route.

Following the Enclosure Act in 1854-5 Great Kingshill did not change very much in the next 50 years. The 1897 Ordnance Survey Map showed a mere 80 dwellings in the village, excluding Cryers Hill and Knives Lane. There were only four buildings on the main road (Missenden Road) between the Cockpit Road/Pipers Lane crossroads and its junction with Stag Lane. These were The Laurels and adjoining cottage (now demolished), Homelands Cottage (now demolished), The Royal Oak, shown as a Post Office in 1874 and later a Beer House and, finally, The Red Lion, a Beer House which had replaced the old Red Lion on the edge of the old common at the rear. A new church school for Great Kingshill was built at the top of Cryers Hill in 1874 together with a new school at Moat Lane, Prestwood to replace the original school alongside Prestwood Church which must have been bursting at the seams.

The advent of the railways at Great Missenden in 1892 and a new line at High Wycombe in 1906 created new interest in the surrounding villages, including Great Kingshill.

|

|

The census returns from 1841 onwards cast light on the distribution of turners in the area. By this date they are recorded living in High Wycombe, Great Kingshill, West Wycombe and Downley, villages evenly spread across the district. More than twenty bodgers lived in Radnage and Stokenchurch, while Great Kingshill, Beacon's Bottom, Bledlow Ridge and High Wycombe had more than a dozen each. In several of the villages north of Wycombe turning was the only chair employment - Holmer Green, Wycombe Heath, Widmer End, Bryants Bottom and Stoney Cross - while the 'hills' villages, about four miles out of town to the northwest, all have turning as the most important chair-related employment. |

|

The common as it used to be showing the Lion's Tail and Harebells in the deep |

Great kingshill 1900-1950

The number of dwellings in the village, including Heath End and Spurlands End but excluding Cryers Hill and Perks Lane, did not increase between 1874 and the end of the century, remaining at a mere 80 dwellings or thereabouts.

Things began to change at the beginning of the 1900s due almost entirely to the advent of the railways. The Great Central and Metropolitan line came to Great Missenden in 1892. It would have arrived much earlier had it not been for the vested interests of Tyrritt Drake at Shardeloes, Amersham and other land owners in the Chorleywood area who lobbied fiercely against the most obvious and least expensive route along the Misbourne Valley. There had been a branch line of the Great Western line linking Maidenhead to High Wycombe as early as 1854, but it was not until 1906 that a more convenient direct line to Paddington was provided. As a result Great Kingshill, being conveniently situated between two direct lines into London with nearby stations at Great Missenden and High Wycombe, became an attractive location for possible development and it was not long before landowners and investors jumped on the bandwagon.

The sale particulars of parts of the Dormer Estate in 1907 including land at Holmer Green, Heath End, Great Kingshill and Prestwood emphasized the fact that the various sites for sale were within easy reach of Great Missenden and High Wycombe Railway Stations. The frontage land on the south side of Stag Lane between Cockpit Hole and the Common Road junction amounting to 5.5 acres was sold for £550. A much larger area of land of 12.25 acres with frontages to Copes Road and Spurlands End Road was sold for a mere £600 and was obviously not regarded as prime building land in 1907. It is now totally developed. In the same year a separate sale was held of freehold building land fronting the southern side of Hatches Lane, the western side of Missenden Road between Hatches Lane and Homelands Gardens and a new road to be constructed parallel to Hatches Lane and now known as New Road. The land fronting the proposed new road was offered for sale with varying frontages and the first houses were constructed shortly afterwards. Similarly, the plots fronting the Missenden Road were quickly developed; Stanley Cottages adjoining the village hall are dated 1908, as are Myrtle Cottages opposite the Royal Oak site.

In the same period George Biggs and Sons, the local building firm, now well-established with a new builders yard and workshops on land between Cockpit Road and Missenden Road, bought land on the north-western side of Heath End Road to provide housing for their key workers. The first pair of houses, Glenmore Cottages, is dated 1908 and six further pairs of houses followed these as and when spare building materials and labour became available. These two locations, Heath End and New Road, accounted for most of the increase in the number of houses in Kingshill from 80 in 1898 to around 120 in 1925, the date of the next Ordnance Survey.

There were a few individual houses built in various locations during this period and some enlargements or replacements of existing houses. For example, William Weller a member of the Weller's Brewery dynasty of Amersham had purchased Springfields at some time around 1850 and he no doubt enlarged and improved the existing dwelling to suit his requirement. The coachman at Springfields happened to be a certain Billy Brindley, a well-known local sportsman and village character who died in 1943 and his employer William Weller appears, unsurprisingly, as the president of Great Kingshill Cricket Club on the team photograph of 1907.

Similarly, Herman Landau, a London business man, purchased Pipers Corner with a substantial area of land, financing the existing house at Pipers Corner and building Pipers which was occupied by Lieutenant-Colonel Kentish before the 1939-45 war.

In 1907 there was no established hall or focal point suitable for holding social or village events. The inaugural meeting of Hughenden Parish Council for instance was held at Great Kingshill School in 1894 when 70 people packed into one of the three small classrooms. Joseph Lisley of Sladmore Farm took a keen interest in village affairs and sometimes made his largest barns available for village events and the Cricket Club often held social evenings at Springfields. By good fortune and some foresight, Mr. Sharon Turner of Peterley Corner had purchased a plot at the corner of New Road and Missenden Road in 1907 and offered the site for a Village Hall provided that the hall was used for non-political or non-sectarian purposes. Considering the limited size of the population at that time, there must have been a strong community spirit to undertake such a project. The first Trustees of the new hall appointed in 1913 give a useful indication of the leading figures in the village at that time, being Sharon Turner of Peterley Corner, George Henry Biggs, builder, William Remington Brindley of Springfield Cottage, Herman Landau of Peterley Corner and Louise Weller of Springfields (widow of William Weller who died in 1908).

It is sad to think that one of the first public meetings in the new Hall was held to persuade the young men in the village to enlist in the army. Not that they needed much persuading with living conditions at home generally overcrowded and work prospects poor. A new life in uniform, fighting for one's 'King and Country' must have seemed an exciting challenge. Little did they realize what lay in store for them, but the names of the fallen on every village and town memorial in the country tell their own story. The Village Hall was put to happier use with the Peace Day celebrations in July 1919 which lasted over two days and the following year a memorial tablet was unveiled on the front wall of the hall before a large assembly.

Thc village gradually returned to normal and motor transport began to play an important part in village life. In 1920 an enterprising gentleman by the name of Sugg started a motorized transport service between Tylers Green and Beaconsfield Station to replace a horse-drawn carriage. This rapidly grew into Penn Bus Company serving the villages around High Wycombe together with the rival Thames Valley Traction Company. A reliable bus service operated by both companies between High Wycombe and Great Missenden in the 1920s and 30s became an essential facility particularly as only three or four households in Kingshill owned a car. The hills out of Wycombe were a problem in the early days, the very steep gradient at the top of Cryers Hill before its re-alignment in 1938 being a particular challenge. It was common practice for the bus conductor to nip out and place a wood block behind the rear wheel when the driver changed gear and when reaching the bus-stop at the White Lion the driver, equipped with a pair of leather gauntlets, would loosen the radiator cap to allow the steam to escape from the boiling radiator.

The increase in motor traffic heralded the decline of the traditional trades associated with the horse such as blacksmiths, saddle tree makers, wheelwrights, etc. Nash's at the rear of the White Horse public house at Heath End, a thriving wheelwrights business employing some twelve men had virtually ceased trading by the 1940s. Of the several blacksmiths in the area only two survived until after the last war, Hildreths at Knives Lane and Evans at Cryers Hill. In one of the workshops at the White Horse, Billy Anderson had started assembling pedal cycles which became a popular means of getting around between the wars and nearly every household possessed at least one bicycle. Billy Anderson then moved along Heath End Road to establish Anderson's Garage which, together with Clarke's Garage at Cherry Tree Farm, began to service the increasing motor trade.

Mains electricity came to Great Kingshill in 1930-31 and it is now difficult to imagine life in the total absence of electricity, but a continuous power cut say for five or six weeks might give one a good idea. Shortly afterwards mains water was made available to most of Great Kingshill although mains drainage did not appear until the 1960s.

With regard to social affairs, the Great Kingshill Women's Institute had its first meeting in 1926 and thereafter took an active part in village affairs. A local concert party calling themselves 'The Seven Companions' also put on shows in the Village Hall and in neighbouring villages. The Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935 and the Coronation of King George VI were celebrated with gusto, the fancy dress parades proving very popular. The choosing of the local 'queen' to ride in style on a throne carried on a richly decorated farm cart together with her attendants could be controversial to say the least. The cart pulled by horses from Cherry Tree Farm headed the parades which started at The White Lion and finished at the Red Lion.

The three public houses in the village, The White Horse, Red Lion and Royal Oak (The Stag in Stag Lane had ceased trading by 1910) were very much part and parcel of village life between the wars, there being no television, very few wirelesses, as we used to call them and, of course, hardly any cars. Newspapers were brought up from High Wycombe and then distributed by Mr. Dobson, better known as old Dobbie, who took them around to the various pubs on his bicycle.

Life in Great Kingshill in the 1930s was probably fairly uneventful and relaxed until the country was once again plunged into a world war, this time lasting six long years, to be followed by a dramatic expansion of the village in the next twenty years.

Great Kingshill 1950-2003

In 1950 the country was recovering from a long and debilitating war with food rationing still in force and many other goods in short supply. House building had remained fairly static since the 1930s but, following the war, it became clear that some additional permanent housing was urgently required for ex-servicemen and some other local people.

In this area, the old Wycombe Rural District Council was responsible for finding suitable sites for such housing within or on the outskirts of the villages in its area. This was an unenviable task as the price paid for the land under compulsory purchase powers did not, as a rule, reflect the real value of the land to the landowners concerned. At Great Kingshill, it was decided that the most suitable site was a parcel of land fronting Cockpit Road amounting to some three acres attached to Cockpit Hole Farm and planning permission was granted in 1950 for the erection of 18 council houses and bungalows, now known as Cockpit Close. It is hard to believe these houses, admittedly substantially improved and extended, now command in excess of £500,000 a mere seventy years after the original estate of 18 dwellings was built at an overall cost of £13,000.

Some private dwellings were built in the first five years following the 1939-45 war but these were at a much slower rate, as building materials were licensed and not readily available. However, the pressure for more housing, particularly around London, was growing rapidly. In 1944 Sir Patrick Abercromby in his Greater London Plan proposed a green belt some 6 to 10 miles wide to encircle London so as to prevent the outward spread of the London conurbation, but this simply resulted in house builders leapfrogging into the surrounding Home Counties.

The incoming Conservative Government in 1951 had pledged in its manifesto to build 300,000 houses per year for the next 5 years to ease the housing shortage and a newly appointed Minister of Housing and Local Government, Harold Macmillan, ensured that this target was met. South Bucks was a prime location and by 1956 Bucks County Council realised, somewhat belatedly, that there was an urgent problem concerning the haphazard spread of development in the countryside. Accordingly, in 1958, the Council proposed a green belt to cover most of the southern part of the County south of the Chiltern escarpment, In addition to the towns of High Wycombe, Amersham and Marlow, large scale plans were prepared for each village to indicate the limit of development and to establish a green belt boundary around each village. At the subsequent public inquiry into the Green Belt proposed, which lasted several weeks, it soon became clear from the nature of the objections lodged by the various landowners in the Great Kingshill area that the Green Belt had prevented the coalescence of Cryers Hill, Great Kingshill and Prestwood along the route of the A4128. It also meant that there would be added pressure to build within the so-called village envelopes.

The first of the private residential estates to be built in Kingshill was on allotment/small holding land on the north side of Stag Lane in 1954/5, now known as Fairfields. This was quickly followed by further individual estates which, together with substantial infilling along the existing roads in the village, resulted in the transformation of a scattered rural community of around 200 dwellings into a more urban-type settlement of 700 dwellings in the relatively short period of fifteen to twenty years.

There was little that the local planning authorities could do to slow down the speed with which this transformation took place. Successive governments, both right and left, made it crystal clear in various planning appeal decisions that further housing was a priority not to be thwarted. For example in an appeal decision concerning the development of Lanes Holding in Boss Lane in 1965, now known as Limmers Mead, the Government's Inspector observed that 'there was an urgent need for more dwellings in this area which was subject to much housing pressure. Residential development in such areas could not be achieved without avoiding some degree of change in the character of the locality.'

Great Kingshill was not alone, of course, in accommodating this massive increase in developments in this part of Bucks. Prestwood and Holmer Green and to a lesser extent Hughenden Valley have all grown rapidly and, at one period in the 1960s Hazlemere had the somewhat dubious distinction of being rated as the fastest growing settlement in the South East of England. Understandably, some old Kingshillians found it hard to come to terms with such a sudden and dramatic change in their general environment although, unlike some attitudes today, they accepted that there was an urgent need for more houses.

Coinciding with the beginning of the expansion of the village, Hoppers Farm, at one time the original base of the local building firm of George Biggs and Sons in the 1920s, changed hands in 1949 to become a model farm for the breeding of turkeys, primarily for the Christmas period. By 1955 the farm had progressed to the extent that it was producing 86,000 turkeys per year, pre-packed on the farm and ready for the oven, with a total labour force of around 140. It also expanded on to Cherry Tree Farm which was purchased in 1960.

In order to cope with the increase in development, in 1960/61 mains drainage was installed throughout the area and the cesspool emptying vehicles, affectionately known as 'scent bottles', gradually disappeared. Other changes included the erection of a small sports pavilion on the recreation ground in 1957, substantially enlarged in 1995, which became the home of Great Kingshill Cricket Club. The Club celebrated its centenary in 1990 and continues to flourish. The old Village Hall was extended in 1977, partly thanks to funds raised by a hard-working sports and social committee originally formed in 1970. The allotments running along the southern side of the recreation ground were transferred to the Red Lion meadow to allow for a much-needed enlargement of the Common together with, the provision of a new children's playground in 1978.

Great Kingshill Residents Association was formed in 1988, with the desire to promote community activities and protect and improve the amenities and environment of the village. A brand new and attractive Hughenden Parish Council Office was built in 1999 on Common Road, looking out over the cricket pitches. The Village Hall, despite its lack of adequate car parking, is still going strong thanks to a dedicated few who give a good deal of their time in keeping it up and running. It continues to provide a welcome venue for various village clubs and other organisations. The Spar shop continues to thrive, providing a valuable service and a much-needed facility for local residents and passing trade.

The physical changes in the village of the last fifty years coincided with the advent of television and the general increase in car ownership. An unforeseen downside to this new mobility was a downturn in trade for the local pubs. The Red Lion has survived, thanks in part to its provision of a proper restaurant serving dishes made with local ingredients. The White Lion and Royal Oak have both been demolished, making way for more houses. In fact, Royal Oak Mews now occupies the site of its namesake hostelry and contains some thirteen dwellings. Indeed, house building continues all around the village, with new developments springing up on Lowlands Crescent, Hatches Lane, Stag Lane and Spurlands End Road, to name but a few. Perhaps a reflection of the continuing high demand for housing, it is not unusual for one large house to be pulled down to make way for several new dwellings, albeit with much smaller gardens. Clearly living space takes priority over land in modern day Great Kingshill, standing in stark contrast to its rural beginnings.